Lancaster and Morecambe Bay have long been shaped by waves of pioneers, settlers, and innovators whose vision and resilience left an enduring mark on the region. From Roman and Viking arrivals to medieval merchants and Victorian industrialists, each era brought new ideas and enterprise that transformed this coastal landscape. Lancaster thrived as a hub of trade and craftsmanship, while Morecambe grew into a celebrated seaside resort, famed for its Art Deco elegance and cultural vibrancy. Today, their legacy lives on in historic landmarks, maritime traditions, and modern projects like the forthcoming Eden Project Morecambe, reflecting a spirit of innovation that continues to turn the tide for future generations.

Lancaster's Roman Foundations

The Romans helped shape the Lancaster we know today, building a fort around AD 80 on the hill overlooking the River Lune. This became the beating heart of a growing settlement. One of the earliest characters tied to the town is Insus, a cavalryman immortalised on a striking memorial stone unearthed in 2005. You can still see this piece of history today at Lancaster City Museum. Insus was a Treveran auxiliary trooper, and he is depicted here dramatically holding the severed head of a defeated enemy — a rare and vivid scene of military triumph.

The Romans first stormed Britain in AD 43, and Lancaster blossomed when the fort attracted a bustling little town, its soldiers providing a ready market for local goods. Even Lancaster’s name tells the tale: recorded in the Domesday Book as Loncastre: “Lon” for the River Lune and cæster, borrowed from Latin castrum, meaning “fort”. A name born from stone walls and centuries of history.

IMAGINE ROMAN LIFE IN LANCASTER...

You can visit Lancaster City Museum on Mon, Tues, Fri, Sat, Sun 10.30am - 4pm.

Tickets are £5 for visitors from outside the Lancaster District.

Lancaster’s Roman Bath House, unearthed in the 1970s at Vicarage Field, was once part of a grand courtyard building – probably home to a Roman official. Complete with a clever hypocaust heating system, it offered a taste of ancient spa luxury in Britannia. Around 340 AD, the bath house was demolished to make way for a mighty stone fort. Today, the Wery Wall – a chunky remnant of that fort’s bastion – still stands proudly on Castle Hill. These ruins not only showcase Lancaster’s Roman roots and strategic importance but also remind us that the Romans knew how to mix relaxation with serious defence.

NOW WALK IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ROMANS...

You can visit Lancaster’s Roman Bath House any time, although it's best to view during the daytime! It is located here and can be accessed via the path to the rear of Lancaster Priory.

Viking Settlers

In the 9th and 10th centuries, sleek Viking longships skimmed across the Irish Sea and bold Norse adventurers set their sights on Morecambe Bay and Heysham. These fearless settlers didn’t just raid, they stayed, leaving their mark in place names and remarkable and in a vibrant coastal culture of fishing, farming, and maritime trade.

One of the most breath-taking relics is the Heysham hogback stone, a 10th-century masterpiece carved with twisting beasts and mysterious symbols. It speaks of Viking beliefs about death and the afterlife, and of a fascinating cultural fusion where Norse traditions met early English Christianity. This blend is beautifully echoed at St Peter’s Church, perched above the bay on a site of ancient worship. Inside you can find the hogback itself, a haunting reminder of a world where faith, myth, and seafaring courage collided.

Perched on the wild headland at Heysham, the rock-cut graves near the ruins of St Patrick’s Chapel are like something straight out of a mystery novel. Carved into solid sandstone, these six coffin-shaped hollows look out over the shimmering sweep of Morecambe Bay. They’re aligned east - west in true Christian style, but their dramatic cliff-edge setting has sparked endless speculation: were they Viking burials, resting places for saints, or something even stranger?

STEP INTO HISTORY IN HEYSHAM...

Visit Heysham and try our self-guided Heritage Walk, taking in the main landmarks.

Call into St Peter's Church to see the famous hogback stone. The church is usually open Monday - Saturday 10.30am - 3pm.

In the summer, visit Heysham Heritage Centre - check their website for opening times, which may vary due to volunteer availability.

Come along to the Heysham Village Viking Festival on July 18 and 19!

The Normans

After the Battle of Hastings in1066, Lancaster became a key gateway to England’s north-west. The Normans wasted no time stamping their authority, raising Lancaster Castle on the bones of the old Roman fort. At first, it was a timber stronghold, but by around 1170, it had transformed into a formidable stone fortress with a mighty keep. More than just a military bastion, the castle became a proud symbol of Norman power: commanding trade routes and keeping the region firmly under their grip. Over the centuries, it evolved into the beating heart of local governance and justice, shaping Lancaster’s destiny for generations.

Roger de Poitou was one of the architects of Lancaster’s medieval story. Gifted vast lands in Lancashire by William the Conqueror, he is believed to have built the original, temporary wooden motte and bailey castle (or ringwork) at Lancaster around 1093 to 1094 to establish control over the region. He also founded Lancaster Priory in 1094, a Benedictine priory linked to a Normandy abbey, on the site of a Saxon church. Inside the priory you’ll find stunning medieval features, like the 14th-century choir stalls, that survived centuries of change, including Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. Today, this Grade I listed church is a living piece of Lancaster’s past, offering a chance to attend one of its worship services, to marvel at the wonderful architecture, or to enjoy one of the regular concerts.

Roger de Poitou's influence stretched far and wide, fortifying strongholds and securing Norman rule across the north-west. Though his fortunes eventually waned, Roger’s legacy remains etched in history as a founding figure of Lancaster’s Norman era: a man whose ambition helped define the region’s future.

DISCOVER BUILDINGS WHICH HAVE STOOD THE TEST OF TIME...

Visit Lancaster Castle and take a guided tour with one of the knowledgeable and inspiring guides. Tours run daily 10.30am – 3.45pm at frequent intervals throughout the day, and you can book your tickets on site. Adult tickets are £9.

The Police Museum (Thursday to Friday only), Witches’ Exhibition, castle courtyards and cafe can be accessed free of charge and without joining a guided tour.

Explore the history and architecture of Lancaster Priory - normal opening times are 10am-4pm Monday – Saturday and for services on Sunday.

Lancaster's Charter

In 1193 John, Count of Mortain (later King John) granted the town its very first royal charter, a game-changer that set Lancaster on a path to prosperity. With this charter came privileges including the right to host a weekly market. Suddenly, Lancaster became a magnet for merchants, traders, and bustling crowds from all around the region. These lively gatherings didn’t just boost trade, they transformed Lancaster into a thriving hub of commerce and community. Over time, these rights gave the town more independence and prestige, paving the way for Lancaster to grow into a self-governing borough.

Today, the granting of the charter is celebrated on Lancaster Day (12 June) with events, activities and a town crier! The charter itself is held in the Lancashire Archives in Preston.

TRADE MEETS TRADITION...

Browse Lancaster Charter Market every Wednesday and Saturday from 9am – 4.30pm for everything from local produce to international cuisine, fresh fruit and vegetables to plants and flowers, jewellery and clothing to arts and crafts.

If you are visiting on or around June 12, browse our What's On pages for details of Lancaster Day events.

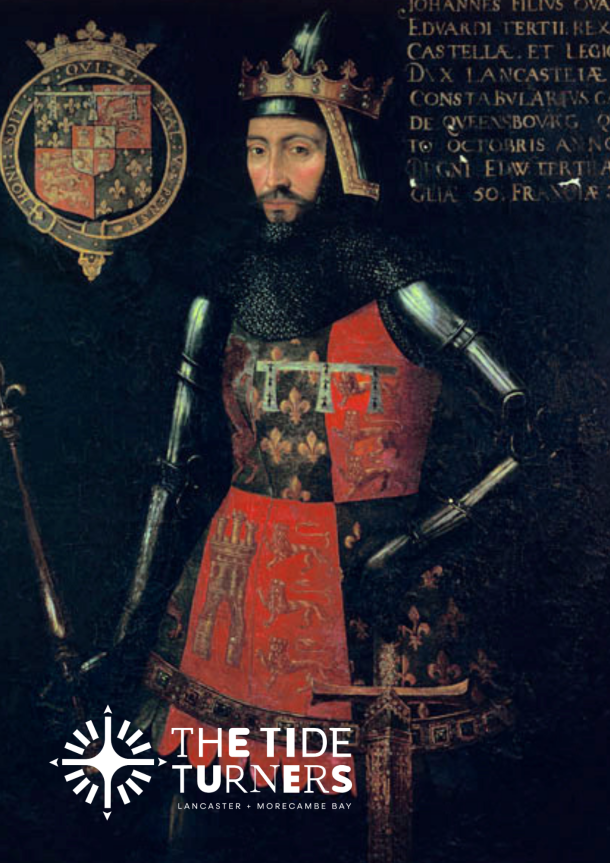

The Legacy of John o’ Gaunt

John o’ Gaunt wasn’t just a name carved into Lancaster’s history – he was a medieval influencer! Born in 1340 as the son of Edward III, he became Duke of Lancaster and one of England’s most powerful figures.

Through his marriage to Blanche of Lancaster, he founded the House of Lancaster, paving the way for his son to become King Henry IV. A fearless military leader, John led campaigns in France and even chased a crown in Spain, while at home he steered the kingdom during times of crisis. He was also a patron of culture, backing literary greats like Geoffrey Chaucer.

As the Duke of Lancaster, he significantly strengthened and expanded Lancaster Castle during the 14th century, adding the impressive two-towered gatehouse that bears his name. But although he was owner of the castle for over 30 years, it is said that he only visited the area himself on a couple of occasions.

Despite this, his legacy lives on in the castle he fortified and through the lands and influence of the Duchy of Lancaster.

A NAME TO REMEMBER...

Lancaster Castle (tours running daily) is the obvious place to visit to find out more about John O'Gaunt - the imposing gateway he commissioned will greet you as you walk up Castle Hill.

But if you're in the mood to sit back with a drink and listen to some live music, call into the pub bearing his name, Ye Olde John O’Gaunt on Market Street! A Grade II listed building, this historic pub dates back to 1871 and has been a hub for social life and live music for over a century, retaining its rustic charm and Georgian character.

Transatlantic Trade

In the 18th century, Lancaster was Britain’s fourth-largest slave-trading port: a fact that casts a long shadow over its history. The city’s wealth and growth were fuelled by merchants such as Abraham Rawlinson, Charles Inman, and Thomas Hinde, who profited from the transatlantic trade in enslaved people. Ships sailed from Lancaster laden with goods, returning with commodities like sugar and cotton - products built on human suffering. These fortunes shaped the city’s elegant Georgian streets and grand architecture, but their origins are deeply troubling.

Today, Lancaster confronts this legacy head-on. Projects like Facing the Past critically examine the city’s role in slavery, sparking conversations about memory, responsibility, and justice. Through exhibitions, research, and public engagement, these initiatives aim to tell the full story, acknowledging the harm while educating future generations. It’s a chapter of Lancaster’s history that demands reflection, reminding us that behind the prosperity of the port lay lives exploited and voices silenced.

Image of Facing the Past exhibition at Lancaster Priory by Rob Battersby.

EXPLORE THE DARK LEGACY OF OVERSEAS TRADE...

Visit Lancaster's Maritime Museum on St George's Quay to find out more about trade with the West Indies. The Museum is open Mon, Fri, Sat, Sun 12pm - 4pm. Tickets are £5 for visitors from outside the Lancaster District.

Explore Facing the Past's map showing the locations and events connected to Trans-Atlantic slavery.

Walk down to St George's Quay to view the Captured Africans Memorial (opposite The Three Mariners pub), a thought-provoking piece by Kevon Dalton-Johnson.

Victorian Visionaries

· Richard Owen (1804–1892)

Lancaster’s own trailblazer of the natural world, Owen coined the word “Dinosauria” in 1842 and reshaped how Victorian Britain thought about life on Earth. A brilliant (sometimes formidable, and sometimes controversial) scientist, he helped drive the creation of London’s Natural History Museum, ensuring that awe‑inspiring collections were opened up to the public.

His legacy still ripples through the city: Lancaster City Museum's display spotlights his work in palaeontology, while family‑friendly events such as Dino Fest (organised by BID each July) bring hands‑on fossils and expert talks to Lancaster.

He also played a key role in improving life for people in Victorian Lancaster. His report on housing conditions highlighted how dirty and overcrowded many homes were, and it helped pave the way for better housing, new cemeteries, and access to clean water.

Listen to Lancaster City Museum's podcast all about Richard Owen and his discoveries and then visit the museum on Mon, Tues, Fri, Sat, Sun 10.30am - 4pm.

Check our What's On page for details of Dino Fest in July.

· James Williamson, 1st Baron Ashton (1842–1930)

A prominent Victorian industrialist, James Williamson built on his father’s manufacturing roots to create a vast textile and linoleum enterprise in Lancaster. Growing a coated fabric business to a vast enterprise which included flooring production and facilities for embossing and printing, he eventually became one of the richest men in the world.

His success in textiles and linoleum production fuelled his landmark gifts to the city such as the Ashton Memorial in Williamson Park. Built as a tribute to his late wife, this striking Edwardian landmark dominates the skyline and remains a lasting marker of local pride. Framed by sweeping parkland and visible for miles, the Memorial hosts events, exhibitions and weddings, and is also frequently lit in colour to mark causes and moments of remembrance.

Lord Ashton also gifted the city its Queen Victoria Memorial statue which stands proudly in Dalton Square. Designed by Herbert Hampton, the monument features the queen atop a grand Portland stone pedestal, surrounded by bronze lions and allegorical figures of Freedom, Truth, Wisdom and Justice. Look closer at the bronze frieze and you’ll spot 53 prominent Victorians – and five have strong Lancaster connections: industrialist James Williamson himself, scientist Edward Frankland, pioneering biologist Richard Owen (as mentioned above!), philosopher William Whewell, and anatomist William Turner. These local legends share space with national icons like Florence Nightingale and George Eliot, making the memorial a fascinating blend of civic pride and Victorian grandeur.

Visit the Ashton Memorial in Williamson Park - open daily from 10am subject to events / weddings! Entry to Williamson Park grounds and the Ashton Memorial is free.

Walk to Dalton Square to view the Queen Victoria Memorial statue with its prominent Victorian figures. Lancaster Town Hall is also situated here. The Town Hall hosts regular events in its stunning Ashton Hall.

Find out more about the memorial statue with Lancaster Civic Society's excellent guide.

· Waring & Gillow Furniture Makers

Waring & Gillow began as Gillows of Lancaster, famed for exquisite craftsmanship and clever designs like the extending dining table and bureau bedstead. By the late 19th century, the firm expanded beyond furniture and, after merging with Waring in 1903, opened chic showrooms in Paris, Madrid and Brussels, even furnishing luxury ocean liners. War changed everything: during WWII, Lancaster workshops produced military supplies, and post-war decline in sea travel ended those contracts. Taken over in 1962 and later absorbed into Allied Maples, the Gillow name faded, but its legacy lives on in museum collections including that of Lancaster's Judges' Lodgings.

The Judges' Lodgings is open on Fridays 11am - 4pm throughout the winter. Then from the beginning of April until mid-November, it is open Thu - Sun 11am - 4pm. Adults £5, Children free.

Visit Leighton Hall, the ancestral home of the world-renowned Gillow furniture family. The hall is open from1st May to 30th September: 1.30pm – 5.30pm (Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday). Tickets £13 for adults, £8 for children.

Art Deco Innovators

The Midland Hotel isn’t just a building, it’s a statement of style and optimism. Opened in 1933, this Art Deco masterpiece was designed by visionary architect Oliver Hill and commissioned by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway as a beacon for Morecambe’s seafront. Its sweeping curves, sunlit terraces, and elegant interiors captured the spirit of the interwar years - a time when modernity promised progress and leisure was a luxury to be celebrated.

Inside, the hotel showcased the work of renowned sculptor Eric Gill, whose striking reliefs and decorative details added artistic flair to the bold geometry of Hill’s design - some of which can still be seen today. Restored and reopened in 2008, it continues to draw visitors who come for its timeless elegance, its rich history, and its unrivalled setting overlooking the sands and sea. It’s a living piece of architectural heritage - a reminder of an era when design dared to dream big.

A DATE WITH ELEGANCE...

Treat yourself to a meal or drink whilst overlooking the bay at The Midland Hotel. Open to non-residents, it's the perfect place to soak in the Art Deco atmosphere and stunning views!

An Entertainment Icon

Eric Morecambe – born John Eric Bartholomew in Buxton Street – remains the beating heart of Morecambe’s cultural identity. Taking his stage name from his hometown, Eric rose from local venues and school halls to become one half of Britain’s most beloved comedy duo, Morecambe and Wise. Their TV specials in the 1970s drew millions of viewers and cemented Eric as a national treasure. Today, his statue on the promenade is a magnet for visitors, a place where fans strike the famous “Bring Me Sunshine” pose against the backdrop of Morecambe Bay. His influence stretches beyond laughter – Eric’s story embodies the town’s spirit of creativity and resilience, making him a symbol of seaside entertainment heritage.

And 2026 marks a milestone: the 100th anniversary of Eric’s birth on 14 May. Plans are already in motion for a year of celebrations that promise to put Morecambe in the spotlight. Expect a joyful tribute that will not only honour Eric’s legacy but also showcase Morecambe as a vibrant, welcoming destination.

DANCE WITH ERIC!

Visit the Eric Morecambe statue on Morecambe Promenade, part of the TERM Project of artworks, and take a photo with him in his famous dancing pose!

If you are visiting around 14 May, browse our What's On pages for details of events taking place to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Eric's birth.